Thriving Outdoors in Cold Weather (Part 1)

Spending a prolonged amount of time outdoors presents a unique set of challenges. Staying warm and comfortable in extreme cold takes more than just throwing on the warmest clothes you own. Whether you're an outdoor enthusiast, a seasoned adventurer, or just someone trying to navigate the freezing winter months, understanding the ins and outs of cold weather gear and effective layering can make all the difference.

This post is the first in of two posts covering cold weather gear.

In this post we’ll be covering the science of cold, how layering works as well as the dangers and injuries that can be caused by cold exposure.

The next post will focus on the layers themselves, how to choose materials and the tradeoffs when using a certain material. Finally, I’ll provide some products I recommend.

We're going to break down the essentials of staying warm and dry at temperatures at, or bellow, zero. Drawing on the expertise of military pros and outdoor experts, we'll reveal the strategies and equipment that have been proven in some of the harshest cold weather environments.

Surviving in cold weather environments presents a unique challenge. Cold weather relentlessly saps your body's thermal energy, ultimately leading to the dangerous condition of hypothermia. It's an inevitable battle that no clothing system can entirely win; some heat loss will always occur.

To counteract this heat loss, your body must burn calories to maintain its temperature. This can be achieved through movement or rapid muscle contractions, commonly recognized as shivering. However, when you've depleted your energy reserves and can no longer generate heat, maintaining your body's warmth becomes impossible, and survival becomes precarious.

Cold, in essence, is the natural state of things, with an absolute zero temperature of -273.15°C, as measured in space, representing the ultimate level of coldness. Therefore, there's no such thing as "cold energy" – only heat that can raise the temperature of objects above this extreme cold baseline.

The sensation of freezing occurs when our body struggles to maintain its core temperature of 37°C. It's important to note that feeling cold doesn't automatically translate to hypothermia, which is a more severe condition.

In the temperature range between 36.9°C and 35.1°C, discomfort sets in. Even when our core temperature is within a healthy range, our skin's sensory receptors can make us perceive a sensation of being "cold." This discomfort is particularly noticeable when we're stationary. The good news is that, just like adapting to any sensory experience, our body can acclimatize to this feeling if regularly exposed to cold conditions.

However, when our core temperature starts to drop, we begin to feel uncomfortable, and our body goes into overdrive to generate additional heat, leading to a natural urge to move. Simultaneously, our brain signals us to seek shelter and warmth. Once our core temperature continues to decline, the risk of progressing to hypothermia becomes imminent.

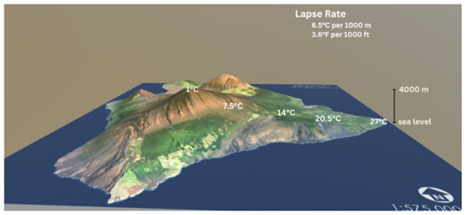

While the distance from the Earth's core generally results in nearly imperceptible changes in environmental temperature, elevation is a significant influencing factor. As you ascend in altitude, the atmosphere becomes progressively thinner, diminishing its ability to conduct heat effectively, and subsequently, the air becomes less warm.

A useful rule of thumb is that for every 1000 meters of elevation gained, the temperature tends to drop by approximately 6°C. This principle implies that even minor changes in elevation can make your surroundings noticeably cooler, with a variance of one to three degrees colder than what you might be accustomed to in lower-altitude environments.

The conversion is also true for depressions or lower-altitude areas; for every 1000 meters of depth, you can generally expect the environmental temperature to rise by approximately 6°C. These elevation and depression-related temperature fluctuations can have a substantial impact on the local climate and conditions.

Understanding Wind Chill

The concept of wind chill is rooted in thermodynamics.

There's a common misconception that the wind itself is colder than the surrounding temperature. In reality, the wind shares the same temperature as the outdoor environment.

The real challenge lies in the fact that every gust of fresh air carries away heat from your body. As a result, your body loses heat rapidly when exposed to wind. In the short term, this can lead to discomfort or even numbness due to wind chill. Over an extended period, you may begin to experience the effects of freezing, as your body struggles to compensate for the heat loss.

To combat wind chill, you don't need a substantial amount of insulation. Materials like dense woven nylon or three-layer laminates such as Gore Tex can serve as effective windstoppers, helping to minimize the heat-robbing effects of the wind and keeping you warmer in blustery conditions.

Understanding Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics encompasses the fundamental principles governing the transfer of heat energy. Since coldness represents the natural state of everything, it can't be transferred itself. However, various objects and gases possess different abilities to conduct thermal energy, commonly known as heat.

Air, for instance, is a relatively poor conductor of heat, which is why heat loss becomes more pronounced when you encounter more efficient conductors like water. Thermodynamics always come into play when one element makes direct contact with something colder. In such cases, the heat energy flows from the warmer object to the colder one.

In our context, these conductors of heat are elements like cold air, rain, moisture, and sweat. Understanding the principles of thermodynamics is essential for comprehending the science behind effective layering to stay warm and comfortable in cold weather conditions.

Understanding Hydrodynamics

Hydrodynamics might sound complex, but we'll simplify it for clarity. Water always seeks the path of least resistance; it inherently looks for ways to move. We can influence and guide how water moves away from our bodies by understanding this principle.

Let's start at the beginning. When our body produces moisture, the first stage is vaporized sweat, which is water in the form of dispersed molecules. In this stage, it moves upward and attempts to permeate clothing and fabric on its own.

However, when the air can no longer accommodate this vaporized water, we start to get wet. At this point, we're producing liquid water that runs along our body, cooling us more than desired. In fact, excessive sweat can even lead to hypothermia, as it needs to be efficiently moved away from our body.

The process of moving sweat away from our bodies is known as "capillary action." This involves numerous small fibers that wick away moisture due to molecular interactions. This is why it's crucial to have wicking fabrics close to your skin, as they help manage and redirect moisture away from your body, ensuring you stay dry and comfortable in various conditions.

The Role of Centralization

Centralization is a survival mechanism that kicks in when our body struggles to maintain its core temperature. Since blood serves as the carrier of body heat, our body adapts by restricting blood flow to specific areas, such as our extremities and facial features. The initial signs of centralization often manifest as cold fingers.

Even when centralization isn't immediately necessary, factors like wind chill can trigger this response. That's why it's crucial to always cover our extremities and head to preserve heat. Wearing items like long johns or lightweight insulated pants can help insulate our legs, while winter socks, over boots, and felt insoles are effective at maintaining warmth in our feet.

Consuming hot beverages regularly can also contribute to keeping our core temperature up, thereby assisting in preventing centralization. However, it's important to recognize that all of these measures primarily focus on preserving the warmth of our core, which is essential for our overall well-being in cold conditions.

Cold weather injuries

Frostbite

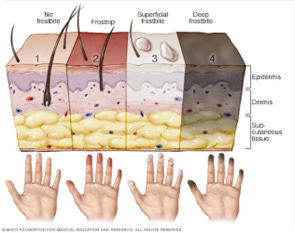

Frostbite, a cold weather-related injury, is often associated with, but not limited to, the presence of hypothermia. At its core, frostbite is the freezing of a part of your body at the cellular level.

It typically begins with reduced blood flow and skin appearing reddish, eventually progressing to the crystallization of tissue and blood due to extreme cold. Thanks to the body's natural centralization response, extremities and facial features, such as the nose, are particularly vulnerable to frostbite.

Frostbite is categorized into four grades, similar to how we classify burn injuries. In the field, treating frostbite involves several steps:

Immediately reduce exposure to wind, rain, and snow.

Gently warm the affected limb or body part with indirect heat, such as placing a handwarmer near the groin area.

Encourage the affected person to drink hot beverages to raise their core temperature.

Dry the affected body part and change wet clothing.

Patients with 2nd degree frostbite or higher require extended medical treatment as soon as possible.

Prompt action and proper care are essential to minimize the damage caused by frostbite and increase the chances of a full recovery.

Trench Feet

Trench feet fall into the category of non-freezing cold-water injuries (NFCWI). It's worth noting that skin irritations with similar names associated with hot and humid conditions are technically not trench feet but referred to as WWIF (Warm Water Immersion Feet).

Trench feet occur due to prolonged exposure to cold moisture, especially when wearing cotton socks and heavy boots, or when snow or water enters the boot. While wicking socks can help mitigate the effects, they should be changed at least once daily. Moisture invariably damages the keratin fibers in your skin, causing tissue damage. This moisture-induced harm is an unavoidable effect, and the only solution is to thoroughly dry the feet.

Trench feet result from the combination of tissue deterioration and capillary constriction due to centralization, a natural response to cold conditions by the body. The best approach is prevention, which includes:

Regular feet inspections

Changing socks at least twice a day

Wearing high-quality socks

Recognizing that drying affected feet alone is not a sufficient standalone treatment

By taking proactive measures, you can significantly reduce the risk of developing trench feet and maintain your foot health in cold and wet conditions.

Chilblains

Chilblains are skin irritations that affect only a certain percentage of individuals when exposed to cold weather. While generally annoying, chilblains are considered harmless. However, they can sometimes be confused with more serious conditions like trench feet or frostbite, which can lead to misdiagnosis and a lack of appropriate medical attention.

Chilblains can appear on various parts of the body, including the hands, face, or feet, further complicating their identification. It's crucial to differentiate them from more severe cold-related conditions. When chilblains affect the nose, hands, or feet, it's important to check for common symptoms associated with frostbite, including:

Numbness in the affected body part.

Skin hardening.

Deterioration of the skin over time.

The presence of black or blue spots.

If none of these symptoms are present, the patient can be given hot liquids and instructed to change socks, gloves, or cover their face to keep warm. Chilblains typically don't require extensive medical treatment. However, if they become excessively large or problematic, they can be covered with a thick bandage if possible.

It's worth noting that chilblains are relatively rare, and those who are prone to them often have prior experience and knowledge about their occurrence.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia occurs when your body is unable to maintain its core temperature. Once the core temperature drops below 35°C, it becomes highly unlikely that an individual can recover from it without the assistance of external heat sources, such as hot beverages, handwarmers, Ready Heat packs, or extensive insulation.

Hypothermia is generally categorized into four degrees:

Mild Hypothermia: Characterized by being awake and shivering, with a core temperature ranging between 32°C and 35°C.

Moderate Hypothermia: Individuals with moderate hypothermia become drowsy and stop shivering, with core temperatures ranging from 28°C to 32°C.

Severe Hypothermia: At this stage, the person is unconscious, with core temperatures falling between 20°C and 28°C.

Profound Hypothermia: In this critical condition, there are no vital signs, and the core temperature drops below 20°C.

Recognizing the degree of hypothermia and providing appropriate care and warmth is crucial to prevent further deterioration and ensure the person's safety.

Essential Preventive Measures

In cold weather conditions, prioritizing prevention is crucial as cold-related injuries can have lasting effects. To help safeguard yourself in the cold, consider these preventive guidelines:

1. Maintain Adequate Caloric Intake: Consume approximately 125% of your caloric needs based on your level of physical activity. A well-nourished body is better equipped to generate and retain heat.

2. Stay Hydrated: Aim to drink at least 6 liters of water a day. Utilize isotonic and hot beverages to maintain hydration and warmth.

3. Active Heat Sources: In static situations, make use of active heat sources like hand warmers to keep warm.

4. Choose Moisture-Wicking Underwear: Opt for moisture-wicking underwear rather than cotton, as it helps manage sweat and moisture.

5. Balanced Layering: Strike a balance between insulating and protective garments to avoid excessive sweating, which can lead to moisture-related cold injuries.

6. Avoid Super Tight Underwear: Tight undergarments can restrict blood circulation, leading to cold-related issues. Choose comfortably fitting clothing.

7. Proper Headwear: Wear suitable headwear to retain heat, as a significant amount of body heat can escape through the head.

8. Leverage Movement-Generated Heat: Use the heat generated by physical activity to your advantage in staying warm.

9. Carry Spare Dry Clothing: Have dry spare underwear and socks readily accessible to change into when needed.

10. Protect Your Legs: Don't underestimate the importance of leg coverage; consider wearing long johns to insulate your lower body.

11. Close Gaps: Seal gaps in your clothing system by using scarfs and gloves to minimize exposure to cold air.

By following these preventive measures, you can significantly reduce the risk of cold-related injuries and maintain your well-being in challenging cold weather conditions.

This is the end of Part 1, Part 2 will focus more on proper layering and actually choosing you cold weather gear.

Stay safe.